‘Death Is Not the End’: The Lost, Castaway Film by Elroy Schwartz of ‘Gilligan’s Island’ fame

The mystery behind his 1975 hypnotherapy-reincarnation documentary and interview with the film’s star, Wanda Sue Parrott

Editor’s Note: In addition to Death Is Not the End, we’ll also discuss the equally lost and production-related, early ’70s films Willy & Scratch and Scream, Evelyn, Scream.

“The mind is an incredible machine, a computer. It stores up all visual, audio, input, the senses you’ve had since the day you were born.” — Elroy Schwartz

Film Documentaries in the 1970s

Stanley Kubrick and MGM Studios may have opened the space gate with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but Charles E. Sellier Jr.’s Park City, Utah-based Sunn Classic Pictures kicked the alien doorway down with their 1973 U.S reedit-reissue of the West German-produced, Oscar-nominated “Best Documentary Feature” and box-office bonanza, Chariots of the Gods? (1970).

In the UHF-TV analog days of the 1970s — the days before U.S cable television channels in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, such as A&E and The History Channel, filled televisions sets with all the dark and weird, paranormal content the curious and the fearful could handle on the dangers lurking within the Earth, in outer space, and within our own souls — the documentary format was a genre cash-strapped exploitation theatrical studios, such as American National Enterprises, Film Ventures International, and Pacific International Enterprises could pull off with self-confidence across America’s drive-in screens. It was all a matter of inserting a talking head here, a fuzzy photo there, a film clip here, some stock footage of Egyptian and Mayan structures there . . . toss in a little electronic Moog noodling there, a Theremin whine there . . . the art department designs a theatrical one-sheet (movie poster) that oversells the film . . . and, with that: the studio crafted a cost-effective, psychological science fiction-inflected documentary — with profits guaranteed.

Four-wall distributing American indie studios and drive-in distributors (the studio rents the movie theatre or drive-in and receives all the box-office revenue) saw the box office possibilities of “ancient astronauts” in films that connected UFOs to the Earth’s architectural structures of old, as well as narratives concerned with clairvoyants and reincarnations, entomology cross-breeding of biblical plague “killer bees,” planetary alignments, and the danger of supercomputers. Tales about presidential assassination conspiracies; that Adam and Jesus were the same spirit, reincarnated; yarns connecting Atlantis to UFOs and The Bermuda Triangle, and The Great Pyramid to The Bimini Wall to the Machu Picchu “space port” in Peru. Investigations on Man’s and Earth’s “untapped energies,” along with aura-capturing Kirlian photography, examinations on plants being able to communicate with humans, telepathy, ESP, firestarters, psychics, and miracle healers. Warnings on the dangers of witchcraft, Satanism, and Black Masses, the perils of Hollow Earth, the reality of a Flat Earth, holes to Hell filled with echoing screams, the biblical destruction of the Earth, Bigfoots, Yetis, black holes, alien genetic engineering of humans, clones, and cryogenic suspension and reanimation.

The paranormal and psychological documentary box-office hits of the 1970s are many: Encounter with the Unknown (1973), In Search of Ancient Astronauts (1973), In Search of Ancient Mysteries (1973), UFOs: Past, Present, and Future (1974), Journey Into the Beyond (1975), Mysteries from Beyond Planet Earth (1975), The Amazing World of Psychic Phenomena (1976), Beyond Belief (1976), In Search of Noah’s Ark (1976), Overlords of the U.F.O (1976), Beyond and Back (1978), The Force Beyond (1978), The Bermuda Triangle (1979), The Unknown Force (1977), Mysteries of the Gods (1977), The Late Great Planet Earth (1978), UFO: Top Secret (1978), Unknown Powers (1978), In Search of Historic Jesus (1979), UFO — Exclusive (1979), UFOs Are Real (1979), and UFOs: Are We Alone? (1979).

While many of these films have been lost to the analog snows of television old and the new digital server screeches of time, some films have resurfaced in digital form via taped-from-television VHS rips by YouTube-users, while others received hard media and official streaming restorations on ad-supported streaming television services like Tubi.

“One hell of a hypnotist.” — Licensed hypnotherapist Elroy Schwartz on his therapeutic, healthcare abilities

‘Death Is Not the End’: The Lost Paranormal Documentary

Then there’s the mysterious, all-elusive film-subject of this cinematic journey— one produced and written by an American television writer the world over knows all too well. In addition to his work on the internationally iconic Gilligan’s Island and The Brady Bunch, we’ve enjoy his comedic pen on The Addams Family, McHale’s Navy, My Three Sons, and Green Acres in the 1960s, and his suspense and action tales on The Mod Squad, The Six Million Dollar Man, and Wonder Woman in the 1970s.

In an April 14, 1977, edition of The Tampa Times, Elroy Schwartz described himself as “one hell of a hypnotist” who claimed he could take his subjects back and forth in time, an ability detailed in his debut book, The Silent Sin: A Cast History of Incest (1971), which served as the basis for his debut, theatrical film, Death Is Not the End: a film shot in 1973 and released in 1975.

During the course of that 1977 interview, Schwartz explained his concept of “procarnation,” a science he explored as a result of meeting Wanda Sue Parrott, an award-winning reporter with The Los Angeles Herald Examiner (existed, 1962–1989). Noted as one of “California’s Psychic Women,” she appeared on local television on several guest occasions, most notably on Tempo, Regis Philbin’s popular, Los Angeles daytime talk show (he became a beloved, U.S national talk show host upon the syndication of his local, WABC-TV New York program, The Morning Show, in 1983).

“If we can go backward in time, why can’t we go forward?” Elroy Schwartz pondered in the wake of the hypnotic sessions he conducted in the late 1960s for his book, The Silent Sin: A Cast History of Incest. “The mind is an incredible machine, a computer. It stores up all visual, audio, input, the senses you’ve had since the day you were born.”

While Schwartz agreed many people viewed hypnosis as “voodoo, black magic,” he believed it served as a legitimate medical tool that could assist in the fields of criminology and dentistry; that an individual can be taught to hypnotize themselves out of headaches and reduce their own physiological pains. It was Schwartz’s contention, which he claimed he successfully achieved as a drug counselor in a California half-way house for girls, he could not only cure, but stop, drug addiction before it happens — through hypnosis. “What if I could get them [hooked] on imaginary heroin, then break them of an imaginary habit?” he told The Tampa Times in 1977. Schwartz claimed he even cured himself from extreme pain to such an extent that he “fooled the doctors” when rushed to the hospital. There, the doctors discovered Schwartz required “three major surgical procedures” and he was “six to 12 hours away from death” as he “kept his vital signs normal” during the medical procedures.

For Elroy Schwartz’s procarnation experiments, Wanda Sue Parrott served as his first test-subject in, through hypnosis, moving a subject “forward” through time. What Schwartz elicited from Parrott’s unconsciousness regarding her “next life” was a horrific, science fiction tale: She lived as a mutant in a post-holocaust destroyed world recovering from an accidental atomic detonation in China. The United States flooded into an island nation, the world was no longer time-designated as “A.D,” but as “I.T,” meaning “International Time.”

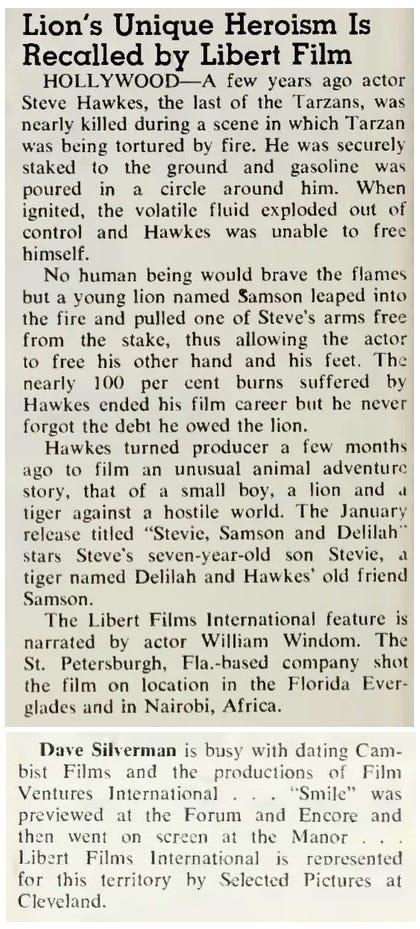

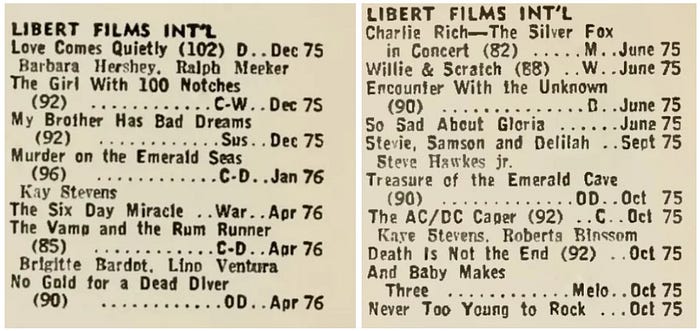

Note the mention of ‘Death Is Not the End’ at the top of the second column. That’s the film’s distributor, Ron Libert, of Libert Films International, seated, third from right.

“These packages may sound like a throwback to the old days of the newsreel and cartoon, but there’s a wealth of exceptional subject matter that best can be presented as the good old-fashioned short subject. The difference is that these featurettes literally should increase boxoffice receipts if properly billed.” — Ron Libert, on his plans of marketing short films to show with feature films, to ‘Box Office,’ February 1975

‘Death Is Not the End’: The Production

Courtesy of the AFI: American Film Institute Catalog referencing past issues of the U.S publications Box Office and The Los Angeles Times from 1975 and 1976, it is learned writer-producer Elroy Schwartz — best known for his work as a principal writer on CBS-TV’s Gilligan’s Island, created by his brother, producer Sherwood Schwartz (years later: Elroy received credit as co-creator), as well as for his comedic writing for Lucille Ball, Bob Hope, and Groucho Marx— then the president of his Writer First Productions, finalized and signed a distribution deal for his paranormal, reincarnation-plotted film, 75 I.T, with Ron Libert’s Libert Films International, in March 1975.

While the film served as his feature film debut, Elroy Schwartz also scripted the feature-length telefilms Money to Burn and The Alpha Caper for Universal Studios. While airing on ABC-TV in the U.S in 1973, each aired as foreign theatricals until 1975, courtesy of the film’s respective, international stars of E.G Marshall, Alejandro Rey, Henry Fonda, Leonard Nimoy, and Larry Hagman. Between 1978 and 1981, Schwartz penned an additional, three Gilligan’s Island telefilms for NBC-TV — again, replayed as foreign theatrical films.

According to a previous, July 25, 1974, report in The Hollywood Reporter, Elroy Schwartz’s long-gestating passion project, 75 I.T, was slated to premiere at the Atlanta International Film Festival in Georgia, U.S.A on August 16, 1976; however, a second report in the December 15, 1975, pages of Box Office noted the film’s actual premiere occurred on December 8, 1975, in Tempe/Phoenix, Arizona. (The Atlanta International Film Festival operated from 1968 to 1974; beginning in 1976, the event relaunched as the Atlanta Film Festival; it seems the festival’s issues scuttled the film’s festival debut.)

According to production materials dated from August 6, 1976, in the AMPAS: Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences library files, when a new releasing company, Dona Productions (actually another Elroy Schwartz-incorporated imprint with Ron Libert), took over distribution, the film’s title was changed to the more marketable, Death Is Not the End.

Elroy Schwartz, then residing as a practicing hypnotherapist in Palm Springs, California, wrote in those 1976 production material documents that “There wasn’t any established script. The movie is a ‘happening’ — a spontaneous filming of a hypnotic regression into reincarnation, and ‘procarnation’ — a look into the subject’s next life.” Schwartz continued in the pages of a December 15, 1975, Box Office issue that Death Is Not the End was a “filmed psychic experience.” In The Tampa Times in April 1977, Elroy explained the unscripted film was “filmed live” in his brother Sherwood’s (Los Angeles) home under the supervision of a medical doctor and, except for time constraints, the film is not edited.

“If we can go backward in time, why can’t we go forward?” — Elroy Schwartz

Ultimately, Death Is Not the End, a 90-minute G-rated film, made its world premiere on December 8, 1975, in Tempe/Phoenix, Arizona, through Libert Films International, with its Los Angeles premiere held on April 11, 1976, through Cougar Pictures (no theatrical one-sheet or newsprint available of the latter showing).

Using those previously noted magazine issues and the AMPAS library files, the editors of the AFI provided a detailed plot synopsis to Elroy Schwartz’s psychological passion documentary — beyond what was described through The Tampa Times in 1977 — a tale concerned with reincarnation, rife with generous amounts of sci-fi concerning nuclear warfare and man’s survival in the post-nuclear age.

While the plot described is begging for some George Pal-styled, H.G Wells-inspired time-lapse photographic reenactments: it seems this is a low-budget documentary that is all-tell and no show — with no narrative recreation inserts. That’s a shame as the post-apocalyptic science fiction described — and that map of “New America” in the theatrical print ads — could be a narrative feature film that would give John Carpenter’s Escape from New York a run for its money.

At his Palm Springs home, August 11, 2010.

“I can’t explain the film you are about to see. I doubt anyone can.” — Dr. Kent Dallett, Professor of Psychology, UCLA

‘Death Is Not the End’: The Plot

A reporter named Wanda Sue Parrott and an African American laborer named Jarrett X are each placed into a deep, hypnotic trance as part of a psychic experiment in past-lives regression therapy — by a licensed hypnotherapist: Elroy Schwartz, as monitored by Dr. Kent Dallet, Professor of Psychology, UCLA.

Wanda regresses to a past life as a young woman in a primitive society (in this writer’s mind: the Eloi from 1969’s The Time Machine by Pal) crushed to death by falling rocks; she then recalls her life as a French male “reborn” in 1659.

Under his own hypnosis, Jarrett reverts to the life of one, Jarrett Elliot Nash: a Mississippi cotton plantation slave in the 1870s. As did Wanda: Jarrett recalls a painful memory of his own death by pitchfork inflicted by the plantation owner’s son.

In the next part of the therapeutic program, Wanda — through “procarnation” exercises where, instead of regressing via reincarnation, an individual “progresses forward” to their next life — becomes a blind mutant born in Cold Springs, Utah, in the year “75 I.T,” a reference to a nuclear holocaust in the year I.T, aka “the Accident,” that divides the United States into the American Islands and the Santa Barbara Islands.

Ruled by the totalitarian World Tribunal of Africa, citizens of the new lands of the American/Santa Barbara Islands cannot engage in scientific experiments, practice religion, or marry without a petition to the government. When Wanda falls in love with a Belgian (Belgium) rebel, she is banished to Russia, which now serves as a prison, with other lawbreakers.

Wanda Sue Parrott, far right (wearing hat), on New Year’s Eve 2025.

“It feels like square blocks were forced through round holes in my brain.” — Wanda Sue Parrott on the procarnation hypnosis therapy conducted by Elroy Schwartz

Interview with Wanda Sue Parrott, Star of ‘Death Is Not the End’

I was beyond grateful to have the pleasure of socializing with the film’s lead actress-subject about her life and career, which included working as an investigative reporter and features writer with The Los Angeles Herald Examiner, as well as her involvement in the film — on the eve of her 90th birthday on February 12, 2025.

What can you tell us about the production of ‘Death Is Not the End’?

I don’t know much about the movie itself at this point. Elroy died a few years ago [June 2013, at 89], following the death of his brother Sherwood [July 2011, at 94]. We shot the film under the title of 75 I.T in Sherwood’s home in West Los Angeles. Ron Libert, whose Libert Films International distributed it, worked directly with Elroy and they retitled it Death Is Not The End [which resulted in the incorporation of the one-film-and-done shingle, Dona Productions, noted by the AFI; the film was shot in 1973].

It’s disappointing when an iconic filmmaker like Ron — with such an extensive resume — has little to nothing about his career online.

As of last year [as far as I know in 2024], Ron is still alive [born in 1931; he’s 94; Ms. Parrott’s renewed, as well as this writer’s contacts, to Mr. Libert received no reply]. Ron was, as was Elroy, very interested in the paranormal. [In addition to Death Is Not the End: two of Ron Libert’s other paranormal films were the Rod Serling-narrated Encounter with the Unknown (1973), and Beyond Belief (1976), which dealt in ESP, paranormal healing, and poltergeists.] Nothing much shows up [online] about his arts or activities, which used to include electronic newsletters from the far, far left, with conspiracy theories, far-out health stuff and Jehovah’s Witness-style religious views. He had a talent agency [New Works Literary Agency] for many years and he was also a writer of various screenplays slanted both toward films and television series.

When did you last speak with Ron?

The last I spoke with Ron was in November 2023. We lost touch as his wife died a year earlier [2024; based on my 2025 socializing with Wanda] and it was very hard on him. He was putting together two episodes of a new television serial and writing a script and [accompanying] book, The Day the River Ran Backwards [about the February 7, 1812, 8.8 magnitude earthquake in New Madrid, Mississippi — when the river ran backwards for several hours]. I’ve never seen the script, in which he says I’m credited as ‘co-author,’ but I only provided him with some research on the New Madrid fault and I am not a co-author. A few years before that project, Ron worked on promoting The Bermuda Triangle into a great mystery; he spoke of his theories regarding ‘the Moon moving away from the Earth.’

I can’t offer information about Kent Dallet and Jarrett X who also worked on camera with me. But Kent was the certified doctor Elroy brought on the film to medically monitor everything. [According to the California Digital Library at the University of California, Dr. Kent Dallett, Psychology, born in 1931, passed away at the age of 44 in 1975.]

Ron Libert, with his wife, at a Jehovah’s Witness revival in 2018.

So, ‘Death Is Not the End’ was your only film role.

I spent 47 years writing a novel inspired by the non-fiction hypnosis experiments that were featured in the film, but leaving out such incidents as Elroy’s hypnotic attempts at getting proof of past lives. I claimed to have lived in France [as a male] and I spoke French on tape, though I do not speak French in person.

[So called] ‘Experts’ at UCLA classified [the language] as medieval French, but academia is full of weirdo Ph. D. candidates who want to believe the unbelievable, so I have no idea if the hypnosis session recorded on tape [for the film] was true. I remember having a dreadful headache when I woke up and I said to Elroy something like, ‘It feels like square blocks were forced through round holes in my brain.’ In other words: I channeled [a] language whose vibrations were not compatible with my brain as a word processor. However, I channel all sorts of things as a writer and poet when I am non-hypnotized. The impressions come and are gone in a flash unless I capture them, which I used to do with my reporter’s notebook and shorthand.

June 1972: Wanda Sue Parrott, center couch, on the Los Angeles KHJ-TV program, ‘Tempo,’ hosted by Regis Philbin. The show ran from 1967 to 1972, airing three times daily at 8:30 am, 12 noon, and 3 pm.

Could you expand on your days as a newspaper reporter?

I was, at that time [of the movie’s production], a newspaper reporter whose unofficial nicknames were ‘the articles and oddities editor’ and ‘California’s psychic reporter’ because parapsychology was my beat.

You also made television appearances and authored books?

In 1973, the year we filmed the movie, I was on television [again] with Regis Philbin in the reporter’s role as one of ‘California’s Psychic Women.’ In 1973, I also wrote my first book for Sherbourne Press. It was titled Understanding Automatic Writing [published January 1, 1974].

Did you specialize in fiction or non-fiction writing?

I was much better at non-fiction than fiction and poetry and finally decided to try writing a novel based on my take from the experiments that led to [Elroy’s] motion picture, but based purely on fictional characters and imaginary sex of a weird nature. It took almost 48 years to complete and I had 100 copies in a Limited Edition made just before the COVID pandemic. They were sold at fundraisers to benefit the homeless men and women of I-HELP at the Unitarian Universalist Church of the Monterey Peninsula. The title is Validiva — The Diary of an Evolving Soul [2017] and you can find it listed on Amazon, if interested. I think it is still available, although it served my purpose in giving me the 100 copies I desired. I am thinking of republishing it with a new cover: a portrait I did of myself at age 23 as an emerging human from an apelike pre-human [1958, image center].

Wanda Sue Parrott, 1961. Wanda attended California Models College in the early 1960s. Deemed too short for high-fashion spreads, she did a lot of catalog, showroom, and trade show modeling before attending university and becoming a newspaper journalist.

I noticed you’ve published under other names, as well.

I have published under at least 18 pen names and have between 55 and 60 books to my credit but not under the name Wanda Sue Parrott. As Diogenes Rosenberg, I am the inventor of the Pissonet form of poetry, aka ‘the world’s shortest sonnet’ and, as Prairie Flower, I helped produce the White Buffalo Tribe series of poetry chapbooks [four volumes, 2011–2013]. After leaving the newspaper business, I taught creative writing in college and was the co-founder/administrator of The National Senior Poet Laureate Poetry Competition for American Poets Age 50 and Older from 1993 through 2014, which is compiled in Golden Words [2012, image right, above].

It seems you never stop creating. What projects are upcoming?

I am currently compiling a fantastic collection of Roswell memorabilia and hope to get it in the hands of a major publisher before 2027, the 80th anniversary of the crash at Roswell in 1947. It will be entitled The Roswell Revelations.

‘Death Is Not the End’: The Distribution

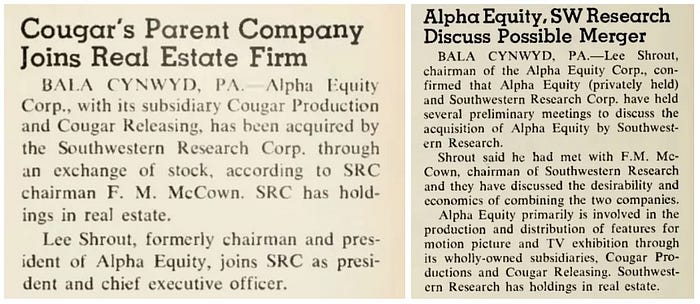

The investigation during the weather-rough, “three-hour tour” to the cinematic desert island that is Death Is Not the End takes us from Ron Libert’s St. Petersburg-based Libert Films International to Lee Shrout’s Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania-based (Philadelphia) Cougar Pictures and, eventually, to Tampa-based producer, writer, and director Robert J. Emery — as well as Hubie Kerns’s International Center Productions that later became affiliated with Cougar — as we fill in the production gaps not covered by the research completed by the American Film Institute Catalog.

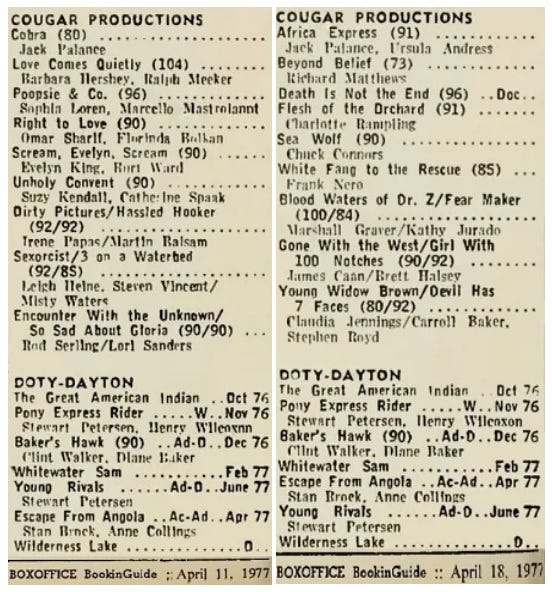

Cougar Productions, the second distributor of Death Is Not the End — again, Libert Films International was the first — didn’t last long. Incorporated in early 1977 as Cougar Pictures, Ltd.— the shingles’ earliest “Booking Guide” section appearance in Box Office was in March as “Cougar Productions”; by November 1977, they listed as “Cougar Releasing”— the company filed bankruptcy sometime in mid-1978, as the company issued their final release schedule in May 1978. By December 1977, Box Office reported Cougar’s assets were assumed by Southwestern Research Corporation.

Lee Shrout, the company’s president, also fancied himself a record producer — in an analogous synergy of American International Records releasing music from films released by American International Pictures ¹ —as the Cougar Records imprint released music from Shrout’s films.

Credited as “executive producer” on Cougar’s releases, Lee Shrout’s most infamous film is the hopelessly lost Scream, Evelyn, Scream (1973/1977). The actual “producer” of the film was Hubie Kerns, who got his start as Adam West’s stunt double on the Batman television series from the 1960s. After Cougar ceased to exist, Shrout continued to “executive produce” films, but actually, only distributed exploitation films until the early 1980s, the Frankie Avalon slasher flick, Blood Song (1982), was his last.

To expand their catalog, Shrout and his Vice President, Richard Nash, purchased the back catalogs of low-budget exploitation distributors. Some of those films were from a Utah regional distributor, Doty-Dayton, who produced G-rated fare like Where the Red Fern Grows (1974) and Baker’s Hawk (1976); the studio was in the same innocuous mindset as Sunn Classic Pictures and Pacific International Enterprises with their G-rated, nature-driven catalogs— and all of those paranormal documentaries, previously discussed. Another failed shingle absorbed by Cougar was International Cinefilm Corporation (that ceased to exist in the wake of the failure of the George Lucas-connected, 1973 horror film, Messiah of Evil).

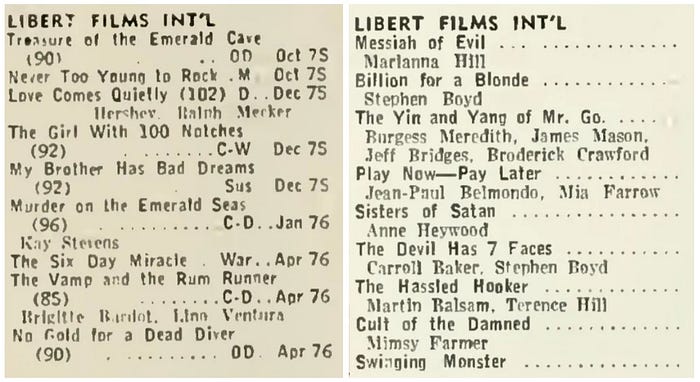

Ron Libert’s Libert Films International, which was around since 1973, ceased operations around that time, so that’s how Cougar came to redistributing Death Is Not the End. Libert had a Roger Corman mindset: he imported Italian and Spanish horror films, then slapped his “executive producer” credit on the product. One of the Italian films Ron distributed in the U.S was Amando de Ossorio’s The Loreley’s Grasp (1973), which he reedited and retitled as Swinging Monster for the drive-ins and later, television.

That’s how American drive-in distribution was done in those days: a U.S producer acquired a European film on the cheap, completed a few edits, and issued the film a new title.

Ron was a smart businessman in that regard. He retained the rights of the films he acquired and replayed them on Florida television and cable stations in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as he lived in St. Petersburg on Florida’s west coast by that point. If the films were part of a national UHF-TV syndication package, is unknown. Most film databases and encyclopedias are incomplete in their cataloging of independent distributors from the 1960s and 1970s: Libert’s and Cougar’s resumes are more extensive than noted, as Ron Libert, Lee Shrout, and another Libert creative associate, Robert J. Emery of American Pictures Corporation, had a lot of fingers in the pie and a lot of logs in the fire.

In addition, Elroy Schwartz’s films four-wall “traveled” with him: at least Death Is Not the End did — from Los Angeles, to Phoenix/Tempe, Arizona, and then to Tampa/St. Petersburg, Florida. DVDs of Dusty’s Trail — both the series and the film cut from it— are easily purchased on Amazon and eBay; it’s his best-distributed theatrical work, not counting his Gilligan’s Island telefilms reissued to hard media.

While Scream, Evelyn, Scream and Death Is Not the End both seem forever lost — another Ron Libert-distributed film, Willy & Scratch (1974), produced, written, and directed by Robert J. Emery, survived.

It was exciting to learn, courtesy of Dawn of the Discs, that Joe Rubin’s film restoration and film distribution company, Vinegar Syndrome, found a print on eBay, of all places, in December 2024, and is in the process of restoration. Obviously, starring the late “1970 Playmate of the Year” Claudia Jennings, known for the drive-in box office hit, ’Gator Bait ² (1973), has a lot to do with that film’s continued interest from cinephiles like Joe Bob Briggs; he kicked the renewed interest and restoration into gear by mentioning the long forgotten film on his social media in 2020.

Now, if the Willy & Scratch hard media restoration is in its R-rated, or X-rated original state— with its infamous pitchfork-in-the-neck scene, in which 11 seconds were cut, and Claudia’s rape scene: who knows what’s on that eBay-purchased recovered print. One may guess the print is probably the UHF-aired television version; again, after their drive-in shelf life: Ron Libert marketed his films to television.

The pitchfork scene not withstanding: Imagine a film containing the subject matter of Claudia Jennings kidnapped and raped — airing on a UHF-TV bred Saturday afternoon, after The Hudson Brother Comedy Hour and American Bandstand?

“Nothing heavy for the brain.” — Robert J. Emery on the production style of his films

As Robert J. Emery explained to Dale Wilson in The Tampa Times on January 24. 1978, the film’s initial X-rating wasn’t for the sex scenes: it was for the infamous pitchfork scene. “I hate violence in pictures. It was hard for me to look at that scene and film it . . . when I got to that portion I had someone else do the filming.” Emery preserved the experience by way of a framed photo of the scene on his office wall — as a teaching moment.

So it goes with U.S theatrical films and television in the 1970s and 1980s where violence against women clears the (then) MPAA censors, but an actor spewing a mixture of Karo Syrup and red food coloring after an implement impalement is frowned upon.

Willy & Scratch also served as the debut release for Ron Libert’s next company, Apollo Pictures/Productions.

The movie itself was produced by American Pictures Corporation, which was Robert J. Emery’s company: based out of Tampa, Florida, he produced, wrote, and directed the film. Meanwhile, Ron Libert lived across the bay in St. Petersburg. Then, after the demise of Libert Films International, Ron picked up where he left off with Apollo. Another of Libert and Emery’s Florida-made films is the Psycho rip, Scream Bloody Murder (1973, aka My Brother Has Bad Dreams), which isn’t lost and easily available on hard media and streaming platforms.

It’s important to note: Regardless of his limited resume in patchy film compendiums, Ron Libert didn’t pop up out of thin air in 1973, only to vanish in the mid-1970s upon the demise of LFI. As were the independent Roger Corman and Herschell Gordon Lewis: Libert was in the business for a long time, starting out in marketing, promotion, and public relations — and that got him into the film business. Another of his St. Petersburg-based companies, Penelope Releasing, distributed adult-erotic materials.

Robert J. Emery made a total of 12 feature films, eight of which were released and “Four never saw the light of day,” he continued to Dale Wilson of The Tampa Times, about his mostly action-oriented films that were “Nothing heavy for the brain.” As with Ron Libert: Emery transitioned into the world of film from advertising, marketing, and public relations. He explained to Wilson that, in addition to operating American Pictures Corporation, he was a producer-director with Image Communications, Inc., a Tampa-based advertising and marketing agency that specialized in local radio and television commercials and other advertising work.

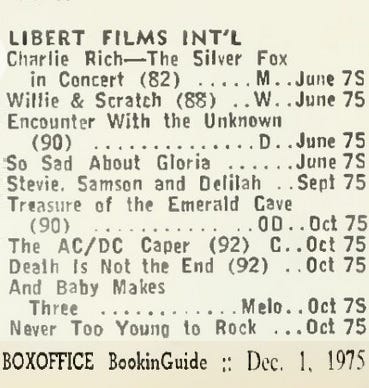

‘Death Is Not the End’ and ‘Willy & Scratch’ appear on Libert Films International’s schedule in October and June. Also note the films ‘Never Too Young to Rock,’ ‘Encounter with the Unknown,’ and ‘So Sad About Gloria,’ which Libert redistributed to drive-ins and UHF-cable television in the late ’70s.

‘Death Is Not the End’: The Crew

While the credits on Death Is Not the End read as a who’s who of classic U.S television —both series and telefilms — from the 1960s and 1970s, it’s important to remember the Schwartz brothers were very successful and well-connected. Elroy brought all of his friends into the project, from the various shows they worked on. A cinephile’s educated guess: everyone — since they were all friendly colleagues, and knowing Elroy’s passion for the “benefits” of hypnosis — worked for free to help the project to fruition.

Larry Heath (died, 2014), and his wife Joan, both who edited, were staff editors for The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, and worked with Sherwood and Elroy during the entire run of Gilligan’s Island. Larry also worked on Dusty’s Trail (1973–1974), the Schwartz’s western comedy with Bob Denver and Forrest Tucker (later cut as the 1976 theatrical feature, The Wackiest Wagon Train in the West). Larry and Elroy worked together on Simon & Simon in the 1980s, as well.

Director Richard Michaels had that same “connection,” dating to Bewitched. He and the show’s star, Elizabeth Montgomery, were an item for a couple of years — and it ended the series. Richard, of course, worked on The Brady Bunch with Sherwood and Elroy Schwartz. According to this writer’s February 2025 contact with the Germany-estate of Michaels: he passed away a few years ago (no date provided).

Cinematographer Alan Stensvold (died, 1981) worked with the Schwartz brothers on Dusty’s Trail, and his career dates to working with Elroy Schwartz on comedian Bob Hope’s television projects.

Alan Stensvold, oddly enough, considering the paranormal content of Elroy’s movie, shot The Astral Factor (1978). He also shot Cyborg 2087 (1966), which — even though it’s a so-awful-it’s-good flick — this writer says Trancers (1984) and The Terminator: Judgement Day (1991) ripped it off — wholesale. Dimension 5 (1966) is another time travel movie on Alan’s resume. Both film’s time-travel elements sound similar to the sci-fi subplot of Death Is Not the End, so it makes sense Alan worked on Elroy’s passion project. (The Astral Factor became part of Cougar’s distribution library.)

Jerry Wineman, the 1st Assistant Director on Death Is Not the End, also worked on The Astral Factor and other projects with Alan. He was primarily a production manager, most notably with my fond childhood memory of Bigfoot and Wildboy, a series that aired as part of The Krofft Supershow Saturday morning block on ABC-TV. Wineman’s career stops after that, in 1979, so he’s probably no longer with us, either.

Hal and Charles Lever, based on their lone “executive producer” credits: it’s an educated guess they worked in the psychology field — and partially funded the project. Most likely, they’ve passed on, too.

“It looked like a switchboard from the 1940s. It was just huge, with all these wires. My mom and I thought that he had really lost it.” — Day Darmet to National Public Radio, June 21, 2019, regarding her father installing a Moog synthesizer in his Laurel Canyon home studio

Then there’s the late Mort Garson’s soundtrack.

Mort is rock ’n’ roll royalty: right up there with the underrated David Axelrod and his rock productions (The Electric Prunes) and fusion-instrumental works. He had a #1 hit with “Our Day Will Come” for Ruby & the Romantics in 1962. Then, there are his records with Brenda Lee and Cliff Richard, and the albums he crafted with Doris Day and Mel Tormé, and Paul Revere and the Raiders. The Doris Day connection is how Mort Garson came to work with Elroy on the film: Elroy was a writer on her sitcom, The Doris Day Show — as well as The Dinah Shore Show.

Once he met American engineer and electronic music forefather Robert Moog, Mort Garson shifted musical gears with the synthesizer — especially on his Lucifer Black Mass album, a work rightfully called a “masterpiece” when it comes to electronica music: the perfect complement to the psychological theories of Elroy Schwartz in Death Is Not the End.

Death Is Not the End: The Soundtrack by Lucifer: one can dream. Another cinephile educated guess: Mort Garson didn’t compose original material; he lent-recycled some older tracks — for free, helping Elroy Schwartz achieve his dream.

More Libert Films International distribution news.

The bottom, October news brief concerns Libert’s representation and distribution by Select Pictures of Cleveland, Ohio, throughout the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, market.

The End of ‘Death Is Not the End’: The Celluloid Castaway

There’s no use in any cinephile finger-crossings, so much so that Elroy Schwartz’s or Ron Libert’s surviving relatives have a 35 mm print or 1-inch Type C, Betacam, or U-matic television tape of Death Is Not the End.

It’s a shame a movie so unique — the only movie ever made regarding the science of Elroy Schwartz’s theorized procarnation hypnosis therapy — is forever lost: a celluloid castaway that a search financed by Wall Street mogul Thurston Howell III can’t find on the bygone, sandy analog shores of a lost, cinematic island . . . but we’ll give it a try, courtesy of documents accessed from the U.S Security Exchange Commission.

According to SEC News Digest newsletters issued by the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission on January 6, 1977, and March 17, 1977: F.M McCown’s Southwestern Research Corporation (itself a real estate holdings company) — which acquired Lee Shrout’s Alpha Equity Corporation umbrella that operated Cougar Productions and Cougar Releasing — had its share of legal issues and related financial problems.

On December 27, 1976, the SEC filed a motion requesting the U.S District Court for the District of Columbia find Southwestern Research Corporation in civil contempt in their failure to comply with an order and injunction issued on June 12, 1975. The order concerned SRC failing to comply with the filing of annual fiscal reports. As the company’s President, Chief Executive Officer, and majority shareholder with 22.8% of stock, McCown was found in violation.³

On February 28, 1977, the Court issued an order finding Southwestern Research Corporation and McGown in civil contempt for failure to file reports required by the Court’s final consent of judgement issued on June 12, 1975. Further failure to respond to the final consent with the filing of proper forms would result in fines equaling $1,000 for each missing report for each day — personally to McCown — as well as $100 for each report and each day directly to SRC, should it fail to file the proper forms in compliance.⁴

While Lee Shrout was not named in the SEC filings, he was, according to articles published in Box Office in December 1977, instilled as the President and Chief Executive Officer of Southwestern Research Corporation.

At that point, through these two SEC filings, the trail on Southwestern Research Corporation, which, again, owned Alpha Equity Corporation, in which Cougar Pictures/Productions was a subsidiary, goes cold. If there was a bankruptcy filed for SRC at that point, as result of the U.S Securities and Exchange Commission judgement, this possibly indicates the related film libraries/assets — which included Death Is Not the End and Scream, Evelyn, Scream; the latter, which Cougar Releasing — according to release schedules printed in the March 21 and April 11, 1977, issues of Box Office — planned to reissue to drive-ins — were assumed by a unknown business entity.

However, Ron Libert successfully reissued other cataloged films under the Alpha Equity Corporation umbrella to drive-ins and UHF television.

As result of the distribution, merger and acquisitions synergies between Libert Films International and Cougar Productions, as well as Cougar’s back catalog of International Cinefilm Corporation releases — which Libert distributed — Ron Libert built a film library with plenty of product to provide to low-rent single/double-screen theatres and drive-ins across various U.S markets. Both films — the main feature and second feature on those bills — belonged to Libert.

A chronicle of TelePrompTer Cable Television is available at Southwest Museum of Engineering, Communications and Computation, Big 13 WTVT Historical Website, and Tampa Bay Broadcasting History Facebook.

As with Ted Turner, a local Atlanta, Georgia, advertising executive seeing the financial potential of the burgeoning cable television market (not a day goes by that we in the U.S don’t watch the Turner-founded TBS, TNT, or CNN), Ron Libert left the drive-in world and entered the cable television business, operating TelePrompTer Cable’s Channel 7 affiliate in St. Petersburg in 1978 (the network defunct in 1981). The station’s programming featured Libert’s back catalog of early 1970s drive-in titles, such as Beyond Belief, Billions for a Blonde, Cult of the Damned, The Devil Has Seven Faces, Encounter with the Unknown, Never Too Young to Rock, Play Now, Pay Later, So Sad About Gloria, Willy & Scratch, and so many more — such as the adult fare of Penelope Releasing in the pay-per-view, naughty overnight hours.

Perhaps, if Death Is Not the End replayed on Ron Libert’s cable channel — there’s no evidence, as such — alongside his other catalogers, someone could have taped it to VHS. Then, cinephiles discover it — as a practitioner of all things Quentin Tarantino usually does with the oddball grindhouse theatre and drive-in flicks of yore later dumped into the VHS ’80s marketplace— years after the-by-accident-fact on YouTube.

The Brady Bunch and Bewitched director Richard Michaels, as the last, failed exhausted research link to the film — if he had any ephemera from, or Wanda Sue Parrottesque memories of the project, if at all — it seems the valiant search behind Elroy Schwartz’s castaway passion project, has ended.

Or has it . . . as Sol Fried’s Capital Productions, in conjunction with Hubie Kerns’s International Center Productions, enters the discussion.

Notice the double-feature theatrical one-sheet for two of Ron Libert’s films: ‘Encounter with the Unknown’ (1973) and ‘So Sad About Gloria’ (1973), as well as ‘Death Is Not the End,’ on the May through December 1975 schedule.

Fin: The Hubie Kerns Connection

The previously mentioned, and lost, Scream, Evelyn, Scream is of interest to fans of ABC-TV’s Batman television series as it features the lone, feature-film starring role for Stafford Repp, who starred in the January 1966 to March 1968 series as Police Chief Miles Clancy O’Hara. The film was produced by stuntman Hubie Kerns through his International Center Productions; he worked as Adam West’s stunt double on the series. Burt Ward, aka Dick Grayson/Robin, also co-stars in the film.

While an article in the March 28, 1970, edition of the Los Angeles Times indicated Scream, Evelyn, Scream, then under its original title, The Date, began production — and makes no mention of Burt Ward’s involvement — a conflicting report in a September 6, 1971, edition of Box Office indicates the film began production. The film received an additional mention — confirming the Los Angeles Times press release— in an April 3, 1970, edition of the industry trade newspaper, Variety, which noted “Burt Ward has been cast by producer Hubie Kerns in the indie film, ‘The Date,’ for which Stafford Repp, Evelyn King, Lance Fuller, and Will Sage, star.”

Based on these three press reports: It is possible The Date lost financing at some point, stopped production sometime in 1970, then resumed production in September 1971, completing production sometime in 1972 — and not 1970, as some film databases indicate. While Hubie Kerns’s debut film, Brother, Cry for Me, was completed and released (and believed to have begun production as The Treasure of Lost Island), the musical, The Melody Man, and Sounds of Summer, never came to fruition.

It is believed that the long-delayed Kerns passion project screened under its original title, The Date, at the 1973 Marché du Film, the 15th annual film market held in conjunction with the 26th Cannes Film Festival, which took place in Cannes, France, from May 10 to May 25, 1973. Any other 1973 screenings beyond the alleged Cannes March debut, is unknown. (There is no documentation to verify the accuracy of this IMDb-allegation or where the information was obtained.)

Hubie Kerns’s debut feature film, ‘Brother, Cry for Me,’ distributed alongside Sol Fried’s ‘Beautiful People’ in the Summer of 1971.

The noted Capital Productions by Box Office was operated by producer Sol Fried and, in addition to his involvement in the production of The Date, he also completed work on Brother, Cry for Me. Fried’s most infamous film is Beautiful People, aka The Sexorcists, aka 3 On a Waterbed (1971) — the latter which appears on Cougar’s March/April 1977 release schedules. As does The Date, Keep Off My Grass!, another Capital Productions’ distributed film, also has a connection to a classic ’60s television series. The counterculture comedy served as the first feature film of Mickey Dolenz since he left The Monkees television series. According to an October 14, 1971, issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Capital Productions acquired the film as part of a three-picture deal with Millennium Pictures. The film was scheduled for wide release in February 1972, with a world premiere in New Orleans in January 1972, the city where the film was shot.

Kerns’s Brother, Cry for Me (1970), Where the Red Fern Grows (1974), and Seven Alone (1974), the latter two produced under the Doty-Dayton banner (noted in the Box Office cover, below) were acquired by Lee Shrout’s Cougar Productions. The films received later, drive-in and television reissues through Ron Libert’s Libert Films International, as did most, if not all, of the films produced under Sol Fried’s Capital banner.

Sol Fried’s ‘Beautiful People,’ aka ‘The Sexorcist,’ were redistributed by Lee Shrout’s Cougar Productions alongside Hubie Kerns’s ‘Scream, Evelyn, Scream’ and Elroy Schwartz’s ‘Death Is Not the End’ in the Spring of 1977.

Scream, Evelyn, Scream (1973) and Death Is Not the End (1975) both appeared on Cougar Productions’ April 1977 release schedule issued in the pages of Box Office. In fact, Evelyn was scheduled as early as March 21 — the first mention of its planned, 1977-redistribution. For reasons unknown, by April 18, Scream, Evelyn, Scream was dropped from the schedule, never to reappear.

One will also notice the Doty-Dayton schedule of films, which included Baker’s Hawk (1976); that film, along with the Cougar-redistributed Encounter with the Unknown (1972) and So Sad About Gloria (1973), also fell under the auspices of Ron Libert’s Libert Films International for drive-in distribution, later to appear on TelePrompTer Cable affiliates in the late ’70s during his cable television years.

The reasons for the 1977 press kit referring to Hubie Kerns as the “founder” of Cougar Productions when the studio was, in fact, incorporated by Lee Shrout — and Kerns’s company was known as International Center Productions and incorporated in 1970— is unknown. The managerial change may be the (assumed) result of the previously noted legal and financial issues related to the U.S Security Exchange Commission rulings; again, by December 1977: Lee Shrout — taking over for F.M McCown — was appointed President and Chief Executive Officer of Southwestern Research Corporation, the rights holder to Cougar’s catalog; Kerns could have been appointed as Shrout’s successor.

Interview: Hubie Kerns, Jr.

Courtesy of the March 2025 insights of Hubie Kerns, Jr. — a second generation stuntman trained by his filmmaking father, he embarked on a successful career in over 1000 commercials, 175 films, and 450 TV episodes — it’s discovered while Scream, Evelyn, Scream never screened in the U.S as planned in 1973, under its original title, The Date, the film did, in fact, screen in foreign markets in the late 1970s under its latter title.

“The film wasn’t released because [my dad] had a crocked distributor [we’ll assume this would be Sol Fried’s Capital Productions back in 1973]. The distributor was given $400,000 for prints. Instead of ordering a limited amount of prints, he ordered hundreds; then fled the country with the $400,000. CFI Film Labs [Consolidated Film Industries of Los Angeles] would not release any prints until they were paid in full. It took years for my father to earn enough money to pay CFI for the prints; he paid off every investor, as well.

“He was finally able to sell or get it released [according to Box Office release schedules: through Cougar Productions in March 1977] but someone at the lab stole a print [unknown lab] and then had it duplicated and released in foreign countries. My father was then unable to get it released [stateside] because it had already been illegally released [explaining why it disappeared from Cougar’s release schedule by April 1977].

“I remember [my dad’s] two car garage being stacked to the ceiling with all the prints he got from the lab. As far as Cannes, I do not know if it was screened — and what happened to all of the prints [from the illegal distribution and the garage]. He worked with a lot of non-mainstream productions; I am not familiar with his involvement with Cougar [Productions].”

The Search Ends

That’s where the search, ends: with the above image of the May 22, 1978, final release schedule for Cougar’s catalog before their 1978 dissolution.

Based on this research, a Willy & Scratch-styled reincarnation of Death Is Not the End — or Scream, Evelyn, Scream for that matter — is highly doubtful.

Who knows what prints of either film are squirreled away in someone’s attic or basement, even garage. The original film lab negative for Alfonso Brescia’s Beast In Space (1980) sat in the basement archives of a Rome movie theatre for years until the original film lab negative was purchased at a bankruptcy auction in Rome, Italy, and restored in 2008 — so stranger things have happened with lost films.

END

Sources:

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences/AMPAS

American Film Institute Catalog/AFI

Box Office, June 21, 1971

Box Office, September 6, 1971

Box Office, February 26, 1973

Box Office, January 6, 1975

Box Office, February 24, 1975

Box Office, April 7, 1975 *

Box Office, August 11, 1975

Box Office, September 29, 1975 *

Box Office, October 20, 1975

Box Office, December 1, 1975

Box Office, December 15, 1975 *

Box Office, December 22, 1975

Box Office, March 22, 1976

Box Office, November 1, 1976

Box Office, December 20, 1976

Box Office, January 16, 1977

Box Office, March 21, 1977

Box Office, April 11, 1977

Box Office, April 18, 1977

Box Office, December 19, 1977

Box Office, May 22, 1978

The Desert Sun, June 17, 2013

The Hollywood Reporter, July 25, 1974 *

The Hollywood Reporter, October 14, 1974

Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1970

Los Angeles Times, April 9, 1976 *

Los Angeles Times, April 18, 1976 *

Tampa Bay Times, March 26, 1978

Tampa Times, April 14, 1977

Tampa Times, January 24, 1978

Tempe Tribune, December 8, 1975

Variety, April 3, 1970

Ms. Parrott’s Interview with R.D Francis, February 2025

Mr. Hubie Kerns, Jr. Interview with R.D Francis, March 2025

Newspapers.com — All newspaper clippings cultivated by R.D Francis

Yumpu — All magazine clippings cultivated by R.D Francis

County Public Library Systems of New York and Los Angeles, and Hillsborough, Sarasota, and Pinellas, Florida, and Montgomery and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

* Asterisks note magazine issues utilized by AFI: American Film Institute Catalog’s research department in their assessment of Death Is Not the End.

[1]: Francis, R.D, May 29, 2024, Medium, “Richard Bowen: The Source and Circle Sound Studios: ’60s Progressive Rock with the Source from San Diego, California” (regarding American International Pictures/Records)

[2]: Francis, R.D, October 28, 2022, Medium, “Ferd Sebastian: A Life in Film: The ’70s exploitation filmmaker behind the drive-in hits ‘Rocktober Blood’ and ‘’Gator Bait,’ passes” (regarding the latter film)

[3]: SEC News Digest, Issue 77–4 (SEC Docket, Vol. 11, No. 4 — January 18)

[4]: SEC News Digest, Issue 77–52 (SEC Docket, Vol. 11, No. 13 — March 29)

Supplementary Research:

- The fiction and non-fiction works of Elroy Schwartz are available on Amazon

- The fiction and non-fiction works of Wanda Sue Parrott are available on Amazon, as well as Great Spirit Publishing and Amy Kitchener’s Angels Without Wings Foundation

- The life of Dr. Kent Dallett, Ph. D. is memorialized on Facebook and the University of California’s California Digital Library with copies of his books discovered on Amazon and eBay

© 2025 R.D Francis. All rights reserved. This essay is protected by copyright and none of its content can be copied, distributed, or reproduced in any form without the author’s prior written consent. Citations and footnotes must be used when referencing this published essay on other articles/essays and hyperlink to this copyrighted source.

The noted interview was edited for length and clarity. All images, press clippings, and photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners.

Inquiries regarding this essay can be addressed to the author at francispublishingmail(at)aol(dot)com.